This work has been deposited on figshare as a PDF and can be cited as

Priego, Ernesto; Eve, Martin Paul (2025). “If you want to make the world better, you’ve got to be prepared to put the groundwork in”: An Interview with Martin Eve on Social Justice and Design Justice in Open Access. figshare. Preprint. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28596383.v3

Abstract

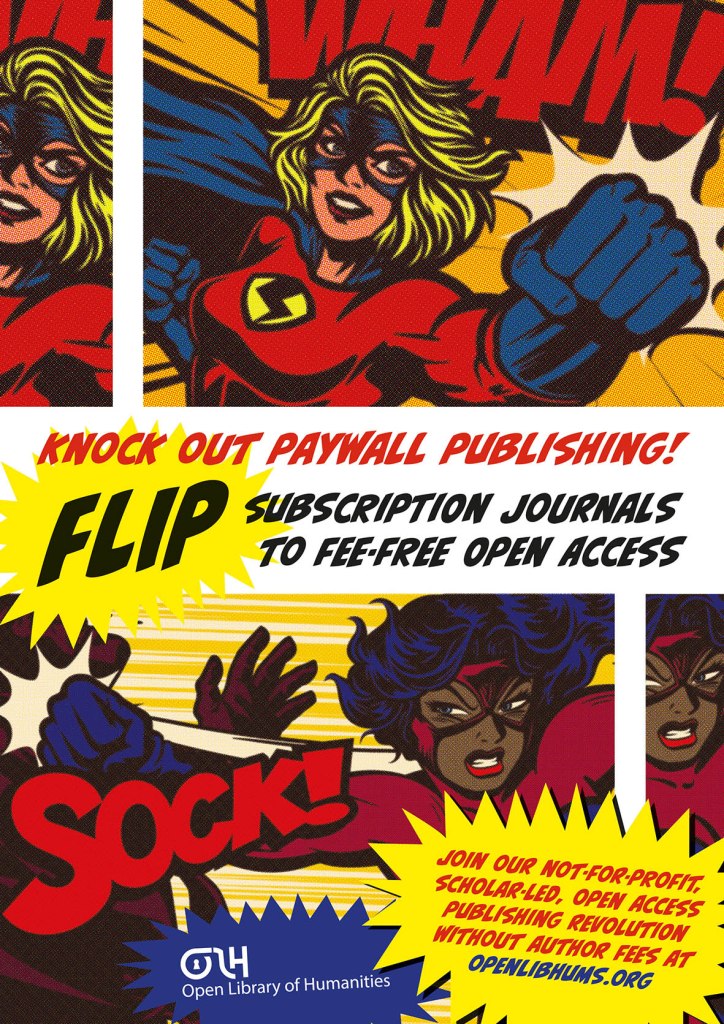

This interview with Professor Martin Eve explores Open Access, social justice, and design justice in scholarly publishing. Eve discusses barriers in academic publishing, highlighting the exclusionary nature of paywalls and Article Processing Charges, advocating for consortial funding models. He recounts the founding of the Open Library of Humanities and the development of the Janeway platform to enable equitable access to research.

Eve emphasises Open Access as a social justice issue, addressing global disparities in knowledge accessibility. He also examines the impact of artificial intelligence on copyright and scholarly publishing, advocating for pragmatic approaches while recognising ethical concerns. Finally, he underscores the importance of design in scholarly communication, arguing that accessibility and usability are central to knowledge dissemination.

Keywords

Open Access; Design Justice; Academic Knowledge Equity; Copyright; AI

On Wednesday, 12 March 2025, I had the pleasure of hosting Professor Martin Eve. It was during the 7th session of the Design Justice module I have led this term. This took place at the Centre for Human-Computer Interaction Design, City St George’s, University of London.

Martin Paul Eve is Professor of Literature, Technology and Publishing at Birkbeck, University of London and the Technical Lead of Knowledge Commons at MESH Research at Michigan State University.Broadly speaking, Martin’s work centres on understanding different registers of knowledge and how they manifest in writing. Martin studies how literary reading techniques can be used to provide us with access to a set of differing epistemologies that all take inscriptive forms: historical, scientistic, digito-factual, and literary knowledges. He is the author or editor of ten scholarly books. Martin is well-known for his work on Open Access and HE policy; he co-founded the Open Library of Humanities and the Janeway platform. As a result, in 2019, Martin was awarded the Philip Leverhulme Prize for Literary Studies by the Leverhulme Trust. In 2020, Martin was elected a Fellow of the English Association, and in 2021, Martin was named by the Shaw Trust as one of the 100 most influential disabled people in the UK. In 2022, Martin was awarded the Canadian Social Knowledge Institute’s Open Scholarship Award and in 2024 was given the Association of University Presses’s StandUP Award.

The interview was conducted over Zoom. This is a copyedited and annotated version based on the automated transcript (Eve & Priego 2025).

Ernesto Priego: Where are you joining us from now, Martin?

Martin Eve: I’m in my home in Broadstairs on the coast. A long way from the University of London, where I normally work, but I hope that we can have a good conversation today about open practices, design, justice, and the social justice issues behind Open Access, publishing.

Ernesto Priego: Thank you so much for joining us. I wanted to ask you first about your background and how did you first get into Open Access?

Martin Eve: I’m an English literature scholar, and it was duuring my PhD that it suddenly dawned on me that the academic job market is absolutely terrible. It’s very hard to get an academic job, which was what I was aspiring to do. I had backup plans to become a computer programmer if that didn’t work. But the thing that annoyed me was that while I was at university, I had access to all this fantastic research, all these resources that came through the university. And I was learning more about the publication system and finding out that academics aren’t paid for journal articles. They’re not. It’s not a revenue source for them or anything by producing these things. But somehow they were producing these things, and then they were being sold back to universities, and when I left I was potentially going to be cut off from that access, and it just seemed to me totally contradictory, because you’ve got people who are working with these lofty ideals about what the university is, for what the point of higher education is doing this research publishing about human artifacts in my case about literature which is open to everyone. And they were publishing this in a way. That meant that only very few people are ever going to be able to read it. I wasn’t going to be able to read it when I left. Academic authors sometimes couldn’t get access to their own material, and it just dawned on me that this whole thing seemed a circular mess of craziness that somebody had designed very badly for thinking about what? Why did we act in this way? And I guess over time my anger at this has subsided a little bit and lapsed into a pragmatism. You know I do accept that. We need the labour of publishers to do certain things that we can’t do or don’t want to do in the Academy, but it just struck me there’s got to be a better way to do this than to cut people off from access and to make it this circular dependency of you publish the work, then you can’t get access to it.

Academic authors sometimes couldn’t get access to their own material, and it just dawned on me that this whole thing seemed a circular mess of craziness.”

Ernesto Priego: How have things changed since? Can you place that historically?

Martin Eve: Yeah. So that was around 2010, I guess. There’s the situation then, which was, you know, almost a decade after The Open Access Budapest declaration [BOAI], but virtually no work in my field was Open Access at that point. It was all paywalled. If you wanted access, you had to go through a provider. Also, I don’t know if people know, but those boxes that sometimes come up with that say you can buy individual access to a journal article- they simply don’t work. You end up on a goose chase, trying to work out how you can actually get access to this thing. You can’t buy it individually if you want to. My friend Ben, who worked at the Higher Education Research Council (HEFCE) for ages tried this on a series of articles and just found it was impossible as an individual to get this access, even though they advertised it, because what they want is the library subscriptions. But if you think about how things have changed since 2010, there is a lot more content in my discipline that’s now openly accessible. It’s probably worth also saying sadly that there are pirate sites that provide a type of Open Access to this material. It’s really funny when people tell me that Open Access will damage the economic standing of publishers and cause problems for them. And I say, well, it’s already accessible, whether you do it or not, through copyright violation. Your work is out there, and it doesn’t seem to have dented what you’re doing and your labour efforts. So, it’s an interesting situation. At the moment, it feels like we’re in a transitional phase in some disciplines. Some disciplines are very advanced in Open Access and almost everything in High Energy Physics, for example, you can read for free. They use arXiv extensively, and that’s great. But other disciplines have been much slower, such as History, for example. But there are signs of this tide shifting. There are mandates from funders. There are academics who are interested in this issue. There are pressures on the Academy to make work accessible and to ensure that the public can read it. But I feel it’s slow. The progress is glacially slow. But there is some shift and change in the attitudes and behaviors of academics towards Open Access.

Ernesto Priego: Can you tell us a little bit about how you started work on the Open Library of Humanities, and then worked on the journal management software Janeway?

Martin Eve: The main problem for Open Access in some disciplines the humanities, for example, is that the economic model is very different to High Energy Physics, for example. There you get a lot of academics getting grants. And if there’s a book processing charge of 12,000 pounds, or an Article Processing Charge of 3,000 pounds, they can very easily put that on their grant and ask the Funder to pay it, because dissemination is obviously part of the goal of those funders. They want the work to be circulated. This model of article or book processing charges is akin to me, saying to the guy on the front row, here, right, I want you to pay 3,000 pounds, and then everybody else will be able to read your work. What it’s done is it’s really concentrated costs on one place, on one person, on one institution. And it said, “you bear the total cost of publication”. This model really doesn’t work very well in my disciplines, which was what publishers were trying to do. They just thought we’ve seen that work in the sciences. We’ll just make it the same in the humanities, and they can pay this. But it turns out that grant funded work just doesn’t happen in my disciplines so much. There are very few grants, and they’re very hard to get. You’ve got a situation where institutions are not wealthy enough to pay this from their English or History departmental budgets. And so, you know, we asked around, we asked humanities academics: “How much could you pay if we had this model?” And they just came back saying, “well, nothing.” Really, my dean would laugh me out the office if I tried to argue that you should give them 3,000 pounds from the budget, just to publish an article, and the next person is going to come along and say the same thing and on and on.

Therefore, we had to come up with a new economic model for what open publishing in the humanities would look like. And that’s where the open library of humanities came from: a desire to implement a new model. And what we decided instead was, if we could get, say, 350 libraries worldwide to pay. I don’t know a few 1,000 pounds each into a central pot. We’d have enough to publish all the material that passed. Peer review that came into us. And we could do that without charging anybody any academic a fee.

So basically, libraries want Open Access. We want to make it work in the humanities and can’t do Article Processing Charges. What do we do? We pull funds from those libraries, you say they want it to work and use those funds to operate and to run our publisher. And so, lots of people said, “this will never work!”. What you’re doing is you’re asking libraries to pay for something that doesn’t give them anything. They cannot participate. And if you publish stuff openly. Everybody will get it, anyway, and that’s called “the Free Rider Problem”. And we just said, “Well, yes.” But as we’ve said, libraries have been driving this quest for Open Access for well over a decade. Now, they really said they want it, so will they put their money where their mouths are and fund us so we can operate, and so that we can get the humanities academics, a space where they can safely publish without those fees blocking their publication. And they did. You know, it took a lot of work, all these projects. If you ever want to build something and make some utopian project that you think will make the world better, you’ve got to be prepared to put the groundwork in, I was traveling to Japan, and one day Edinburgh the next, and San Francisco after that. The next day. It was. It was this very intense period of life where we were getting these libraries on board. but we did it. We’re now stable and funded. I don’t run the open live humanities anymore. I’ve handed it over to a colleague, so you know, we’ve got succession planning. We’ve got continuity. We’ve got sustainability. We built something that I think will now last and is a sustainable contribution to this space.

If you ever want to build something and make some utopian project that you think will make the world better, you’ve got to be prepared to put the groundwork in.”

Ernesto Priego: Could you tell us a bit more about the relationship between what you have described, which is about the Open Library of Humanities as an organisation, that it is offering a different way to fund scholarly publishing, and owning the platform that makes it all possible? When people think about designing an interface, how connected is it to the mission of the organisation, and how specific to the OLH’s mission was the work on Janeway?

Martin Eve: An interesting aspect of the launch was that at that point we needed some kind of bootstrapping mechanism to get off the ground. We had this situation where we didn’t have a platform that we owned. We had potential funder interest and an idea for our sustainable economic model. One of the options was to build our own platform from scratch; our own interface and workflow, but that would delay our launch by a good year. We’d spend a year building software, designing an interface, ensuring it all works. And we’d launch. And this software would be brand new, untested, and we’d be in a difficult situation. What we did instead was that we went to an organisation called Ubiquity Press. That is, a (sadly for-profit) publishing services provider. And we partnered with them to operate our platform initially, to give us basically the publishing services that we couldn’t get immediately and use those as the starting point, and that worked well for a while. It did exactly what we wanted it to do. It got us off the ground. We had a platform that worked and was tested. We didn’t own or control that platform in any way, though, so if there was a change we needed, for example, enhancing disability, accessibility, it became very difficult for us, in that situation of non-ownership, to get that implemented as a priority. We were dealing with a provider who’s trying to cater to multiple clients, multiple competing design priorities on what they’ve got for their platform. It’s not necessarily our ideal situation. But we used that time when we were with Ubiquity to design and build our own workflow platform for what we were doing behind the scenes. We wrote it in Python. Basically, you know, one of the most popular programming languages in the world. This means it’s easy to hire people to work on it, so there was an HR and social decision behind the technology choice. But that platform was built, as I said, over the course of about a year. It started as a weekend hobby project and evolved into a full-time software development initiative. The platform’s called Janeway. It’s a scholarly communications workflow management tool. We own it, control it, understand it, operate it now, and we migrated all our journals to it a few years ago and managed to get off Ubiquity, giving us better cost savings by running our own platform. It’s just been getting better ever since.

The challenge was that we had to build a workflow that worked for scholarly communications, which is a very specific space. There’s really nothing else quite it. It’s not as though you can take a generic workflow platform and just say, right, we’ll use that we had to think about, you know, where does Peer review sit in this, for example There’s debates about whether that should be done before something’s made public or afterwards. For example, Pre-Review. where somebody says that shouldn’t be published, so the article never sees the light of day. Or do you make the work public, so everyone can read it, and then afterwards you get academic opinions on it? Who say there’s some problems with this? Look at this and this and this, and everybody can see the dialogue going on. So, we had decisions about what to do with the platform and its workflow, and where you put review in that status chain. It’s been a really interesting experience building it and learning about different spaces and their demands and the differences between them, and how we can cater to as many as possible with that software.

Ernesto Priego: As a now long-time user, I agree on how well it it’s working, and the improvements have been noticeable in my experience. Moving on a little now towards the idea of social justice. Do you see Open Access as a matter of social justice?

Martin Eve: Yes, I see it as a matter of social justice. I’ll explain why in a second. The interesting thing about Open Access is that there are several parties involved in its realisation, theorization, and creation. Whatever you want you want to call that, people who have different competing ideologies and ideals that they believe Open Access contributes to. It’s at this intersection of a set of different people. There’s a whole group of people for whom Open Access is merely a way in which small business enterprises, for example, can get access to engineering papers so that they can improve their systems, and it helps them, and it’s a very neoliberal economy of they’ll get a benefit from this. They pay tax so they should get access to it, and there’s not much social justice in that angle of things. It might have its own unique benefits. There might be upsides to that view. Maybe it’s good that our small enterprises can thrive and get access to this stuff. But that’s very different to say scholars in South Africa who are saying, “we can’t get access to papers from the global North; our institution can’t afford them. We can’t publish our papers Open Access because we can’t afford the fees that these journals charge”. For me, doing Open Access, unlocks a whole global discourse of academic communication. It lets everybody participate in reading and having access to research in a way that you would not see if you didn’t have Open Access as a principal. And that’s a very different stance to the people who have that small enterprise view. But it doesn’t really matter in a way, because we both want the same thing. We both want Open Access to happen if there are just different motivations behind it. And I think where projects tend to succeed is where you’ve got a practical thing you want to do, and several different political ideologies coming together and saying, “you know what? Although we’re very different in what we believe and why we’re doing this, we think that we actually want to achieve the same thing”. There are Open Access advocates who are very strongly opposed to that view. They think that would be a compromise. It would be a hideous pollution of the ideal situation with Open Access where it’s all just about ensuring that everybody has access, you know, regardless of whether they can pay. So, the poor and the rich, the global North and the global South; the poorest person who’s got access to the Internet and the richest person. But I think that the pragmatic stance is to say, well, so what? That they don’t want it for that reason and have this other goal behind it. We can’t block their other goal. It would be very hard to reconfigure Open Access to make sure that didn’t happen. Let’s work with them to make this a reality.

Doing Open Access unlocks a whole global discourse of academic communication. It lets everybody participate in reading and having access to research.”

Ernesto Priego: Do you see Article Processing Charges as a necessary step? Do they have positive aspects?

Martin Eve: I think that Article Processing Charges are a result of lazy business thinking from academic publishers. It’s always worth thinking about publishing and these type of enterprises as a labour driven organization. There is always labour going on at a publisher that we need that we can’t get rid of that somehow needs to be done somewhere. so that needs to be funded. People can’t work for free. That’s unethical. That’s something we need to think about. What they did was, they said, “right, we used to compensate that labour and make a profit, or whatever we do by selling this material that we’ve published. Each of you will pay a small amount. And essentially, there’s enough money to pay for the labour of publishing that academic article. It sounds like a fairly typical business model. That’s what you had in the sales model. Then we said, “okay we don’t want you to sell that anymore. We want everybody to get access to it without paying to get free access to this material”. And they scratched their heads and said, “okay, but that’s really problematic, because all our revenue comes from people having exclusive access to this and paying us for it. And if they don’t do that, how are we going to compensate the labour?” So, they turn around and said, “well, let’s re-envisage what we do as a service to the people who are coming to us to publish. And we, you know, we get the paper peer reviewed. We typeset it; we copyedit it. We proofread it. We submit the digital preservation. We put it on a platform. We’ll put all those as propositions to an author and their institution, their academic organisation, and say, well, what you should pay this now, because we’re doing it for you. Your work could be disseminated widely, and everyone can read it for free.” Now that sounds good in theory, but they really haven’t thought about that distribution aspect that I talked to you about earlier that if we can spread the cost as a sales model does, and as our OLH consortial model does. You’ve got a much better model that doesn’t have this unequalising effect.

And that’s the real issue. It’s just a real problem exclusion. And that’s a social justice issue. Some institutions, particularly in poorer parts of the world really cannot afford an Article Processing Charge of 3,000 pounds just for a single article. It’s just it’s not going to fly. They can’t do it. But the other thing we know is that, at the moment, we can afford to publish openly all the research that’s published in the world right now. Elsevier, the largest academic publisher in the world, makes 33% or more profit per year on its billions of pounds of revenue. It’s far more profitable by percentage profit than Shell oil, than big Pharma. You know, those are running at 18%, and they’re running at 30+%. There is enough money in the system to make Open Access work. The problem is turning it around, getting it into a central location and then publishing the work based on merit without charging people in a way that they can’t afford. It’s a social problem of organisation, collectivism and pooling resources to achieve the compensation of labour that makes the social justice results of Open Access viable, economically. Might be a little bit complicated. But hopefully I’ve explained that in a clear enough way.

We can afford to publish openly all the research that’s published in the world right now. Elsevier, the largest academic publisher in the world, makes 33% or more profit per year on its billions of pounds of revenue. It’s far more profitable by percentage profit than Shell oil, than big Pharma. You know, those are running at 18%, and they’re running at 30+%. There is enough money in the system to make Open Access work.”

Ernesto Priego: Yeah, that’s great. Thank you. Thought-provoking. And finally, we need to talk about Gen AI in the context of the potential changes to copyright law and the current reactions of, or resistance, from the creative industries. Could you tell us a bit more from your perspective? How do we balance the potential paradoxes between openness, fairness and big corporations potentially, arguably profiting from others’ intellectual labour?

Martin Eve: This is a very tricky area. One of the original goals of Open Access was to open material to text and data mining potentials. One of the arguments made was that having academic material openly accessible made it computationally accessible, and that would yield a new way of searching literature. We might find new things by computational methods to text and data mine. These papers synthesise them into something new and produce novel outcomes through that process. We didn’t know what that would look in 2002, when the Budapest Open Access Initiative was signed. It was just a glimmer on the horizon, but it was one of the things that was thought interesting and promising, and one of the reasons that open licenses were applied in the Open Access space. And it’s actually happened.

Basically, Gen AI training is text and data mining on a massive scale. It’s ingesting tons and tons of material to the point where you have a model where the statistical average can produce useful language for what it’s synthesised. Across all these papers, across all this content that is brought in. But people don’t get it, you know. They say “you’ve stolen my material” when it’s harvested by a Gen AI harvester. Well, that was the goal of some of the Open Access movements! It’s hard to say you couldn’t see that coming, but they have also used material that is not openly accessible that is just available in pirate archives. And you know, that’s potentially difficult. If an author relies on sales of their material and they suddenly see someone using it, they think that’s outrageous. But U.S. copyright law has a thing called Transformative Use. It is a Fair Use provision where, if you do something completely unanticipated with a work and transform it into something that the author couldn’t have anticipated, you are allowed to do that with copyrighted material. That material is there for people to find ways to use that the author didn’t anticipate. If the author thought of it, and wanted to sell it in that form, that’s not acceptable, and that would have been copyright violation. But I’m pretty sure that us courts will rule in the near future that Gen AI harvesting is Transformative Use. It’s something novel that comes out of the use of copyrighted material.

The point of copyright is not actually the individual economic protection that people think it is. It’s to ensure that once that is done and people have had their share of it, the work is publicly available for free forever for everyone. It becomes openly accessible as the default.”

This discourse also hides a lot of misunderstanding about the history of copyright. Copyright is a time-limited right to sell work that expires, and then things become Public Domain. The point of copyright is not actually the individual economic protection that people think it is. It’s to ensure that once that is done and people have had their share of it, the work is publicly available for free forever for everyone. It becomes openly accessible as the default. That was a bargain struck between various publishers and the government in the Statute of Anne [1709] back in previous centuries. This is really all being questioned.

When we come to Gen AI, there are some very bad copyright arguments coming through that don’t understand that history and think that basically copyright should be perpetual forever. And for one person. But my personal stance is AI is not going away. We’re not going to get rid of it. It should be as good as it can be, and it should serve us as best as it possibly can. I think that having high-quality academic papers that have the truth in them available for synthesis and training is a much better way to ensure these things. Do give us a truthful and reliable account when we ask them rather than them going to Reddit and ingesting some horrific content that is completely inaccurate and having that as their training base. I don’t think we’re going to block it, and it’s going to go away. It’s something we have to live with, and we should live with it being as good as possible.

“’m pretty sure that us courts will rule in the near future that Gen AI harvesting is Transformative Use. It’s something novel that comes out of the use of copyrighted material.”

Ernesto Priego: Thank you so much, Martin. Okay, so we have reached the end of our time dedicated to the Q and A. But we have time for a couple of questions from the crowd in the room. Would someone like to ask Martin something in the context of the ideas discussed in the lecture or his talk?

Martin Eve: Someone’s got a hand up.

Student: What’s your perspective on the history of the Internet as a system intended to transfer information and the current landscape of privatisation of the online landscape, in relation to Open Access?

Martin Eve: That’s a really great question. The history of the Internet is quite a complex phenomenon, with the original Arpanet coming out of Stanford when it was first developed. Janet Abate in her book Inventing the Internet (1999), makes it very clear that the original goals of the Internet would serve a military command from a control perspective. They were U.S. Military funded. They had to build a communication network that was resilient and particularly decentralised. We were in a post-Cold War context of the birth of the Internet, and the fear was, well, what happens if we build a centralised communication system that relies on some complete unit in the U.S. Where all communication goes through that it will immediately become a target for any potential military adversary. And if it’s destroyed, our digital communication network falls apart. They were tasked with building a network that was resilient and distributed and could root around any problems that were found in it. But the thing was, you’ve got this very interesting combination of people again, it’s this combination of political ideologies that I talked about earlier. You’ve got people with a military ideology coming together with a hippy intellectual culture at Stanford, of people who believe in the open, free sharing of information that everything should be free and open, and with that social justice mission. But they both want to build a decentralised network that can’t be shut down. One group wants to build it because they think the government will come to them and shut them down. The other group wants to build it because they think that the Russian Government will come and shut down their network, but they both want the same thing at the core of it. They want this open dissemination. And so, you see this gradual network build out from Stanford to other academic institutions, and that’s where they start sharing information between themselves. They’re posting their computer science and physics papers on these FTP servers between the original nodes on the Internet. And from then on, for some people, the logic is just clear. Information and research should be freely shared using these digital systems that allow for infinite replication. Other people who’ve been entrenched in print cultures for decades have a lot of trouble adjusting their mindset to this new digital world and what it offers and what it can bring. I think you’re just right in the insinuation there that the core logic of why the Internet developed and was built contains within itself the logic of Open Access. And the idea that open sharing could be a social justice project of the Internet. And it’s logical to pursue that, given what the technology offers.

For some people, the logic is clear. Information and research should be freely shared using these digital systems that allow for infinite replication. Other people who’ve been entrenched in print cultures for decades have a lot of trouble adjusting their mindset to this new digital world and what it offers and what it can bring.”

Ernesto Priego: I was thinking along similar lines. I think of Aaron Schwartz. You mentioned Stanford there, and he went to Stanford, didn’t he? And I think Lawrence Lessig was in Stanford Law School at that time too. But Aaron was a university student, and you know, he also got to work with Tim Berners-Lee. He was a key activist of free culture, openness as a human right and as a way to make government accountable. And now things have moved towards a situation in which this very same technology has been and is being used in an opposite direction or contradicting those ideals almost.

Martin Eve: Have you have you told the group about Aaron Swartz, and what happened to him?

Ernesto Priego: I only alluded to it very briefly during the lecture.

Martin Eve: It’s just worth saying that. He was a developer of the RSS protocol, the Really Simple Syndication feeds and worked a lot on Creative Commons. But his final project in a set was to download all of the material on Jstor from the academic network he was based in with the suspicion that his goal was to release this, whether it was in copyright or not. Basically, a kind of guerrilla liberation project for information. This all went very wrong. When his downloading script was discovered, the FBI sweeped in on him. He was faced with excessive Federal charges, and he killed himself sadly. Still, basically a teenager. It was absolutely devastating. You know, this pioneer of the Open Access movement and early martyr for the cause in the end. But it does show how strongly copyright is enforced and how authoritarian that the clampdown was against basically a teenager who was trying to do some good in the world, even though it violated copyright law. And it’s an extremely sad case. But it does show there’s no way we can do this in ways that are illegal. We can’t really work around the system as it stands. We’ve got to change the system for it to work properly if we don’t ourselves want to face those legal threats and end up in dire situations.

There was a question on the front row, I think.

There’s no way we can do this in ways that are illegal. We can’t really work around the system as it stands. We’ve got to change the system for it to work properly if we don’t ourselves want to face those legal threats and end up in dire situations.”

Student: Thank you, you’ve answered the question already.

Martin Eve: Okay.

Ernesto Priego: Any other questions?

Student: Yeah, so obviously, there’s monetisation in publishing. And I also think about copyright. And if I remember rightly, copyright was meant to give the author the chance to work, adapt, and improve and create more stuff based upon their work, and they kind of got extended. I’m just thinking that some someone might come up with a way that actually works against Open Access to monetise it. But using some of the principles or something. Is that something that it’s possible?

Martin Eve: Thank you for that question. I guess organizations that run Open Access publishers are not in a very good position to monetise the content that comes in, because essentially, that they’re giving it away for free, and they put an open license on it so other people can take it and redistribute it. And it’s a bit Odysseus binding himself to the mast as he goes past the sirens. They’ve kind of tied their own hands by saying, it’s openly licensed, you know, they’ve made it very difficult to sell, although Open Access book publishers, for example, sell copies of the physical print book that they produce, you know, and they do charge for that. As long as there’s a digital copy openly available, they can sell print. And there’s a demand for that.

Is it fun reading 80,000 words of a book on screen? Not particularly. The print codex and the print volume still hold a huge appeal to people. So that that’s a way they could monetise things. But that’s a way that most authors are pleased to be monetised, they don’t care if you sell their books, they want a print copy. It’s nice to give to your grandma and say, look, I wrote a book, to see people reading it in public, to have it in bookstores. You know this is all good for the dissemination of the work.

And I guess this is what’s different about the Open Access space of academic publishing, and other spaces of publishing or other spaces of work is that academics don’t really expect a direct return on what they publish and produce. What they expect is, if they can get their work published and respected by other academics, and peer reviewed and sanctioned by a publisher who has a prestige factor. They will take that back and either get an academic job as a result of it, or they will be promoted. Or recognised in some way at their institution. So basically, the monetary return for the author comes in the employment status that is conferred by the prestige of the publication. These publications start to serve as a kind of proxy for evaluating people, and whether they’re any good. It’s very odd you don’t get that in, say, publishing a novel. Publish a novel and get it with a prestigious publisher. It’s not going to make any difference, you know. You need to sell it to make money as an author in that context. In the academic context, it doesn’t matter if only 2 people in the world read your paper. But they are really senior people and really important, and it changes a whole field of study. For example, because of what you did. That’s what might get you the kudos to get your promotion and your monetary return centrally. So. I’m not clear that academic authors have the same desire to see various forms of self monetization of what they’ve published. They’re very happy to give that to a publisher and let them monetize it in whatever way they see, because it’s not of value to them until it’s published by the person they want it to be published with. There’s quite a complex symbolic economy basically going on here that maps onto that real economy and makes things tricky to understand. That’s what I think is going on.

I’m not clear that academic authors have the same desire to see various forms of self monetisation of what they’ve published. They’re very happy to give that to a publisher and let them monetize it in whatever way they see, because it’s not of value to them until it’s published by the person they want it to be published with.”

What academics don’t like, though, comes back to the Gen AI stuff we were just talking about. If you publish something with an Open Access publisher, they make it available for free. You’ve given it away in the spirit of good faith. And you’ve done that for public good, for readership, for worldwide global discourse, and so on. And then a for-profit corporation comes along and trains their AI model on your work without any recognition, monetary comeback, and so on. For me, that’s not a problem. For other people it is. They think it’s a very big moral problem and wrong, and they don’t want to do it. I have licensed my work for anybody to use, and I’m afraid that includes for profit for corporations those I agree with those I don’t agree with. But that’s just part of taking the risk of open thinking and open practices. You don’t know who or what is going to do something with your work, and if you surrender the rights to it, you just must go with it and say, “oh, that’s interesting. I didn’t anticipate that happening.”

Ernesto Priego: Thank you; that’s beautiful. Do you have time for one more question from me?

Martin Eve: Yeah, sure go for it.

Ernesto Priego: A question that may be in some of our minds might be, why what does all this have to do with design? Of course, we have referred to very literally to the work on Janeway, right? I will also share later a link to an article from 2020 that evaluates journal management systems, by the way. We were chatting earlier about how some people’s experience of research is that it should be full of friction, that if there’s no friction there is no research work, and that it should be very difficult to access something for it to be valuable. Isn’t the usability of the whole scholarly publishing landscape a big problem?

Martin Eve: Yeah. The term design is a very broad term. We design all sorts of things. We can design systems; we can design interfaces. We can design software. But we always design social systems. We have to think about how do social grouping, social hierarchies, governance structures affect how easy something is or otherwise to use? When you’re designing a software interface, you can’t just sit down and do it in isolation. You must reach out to groups of people you must think about. If you if you’re going to be user centric. You can’t just imagine your users. You must find some of them, talk to them, find out their real-life aspects of what they need from a system and design your social structures to support that. It’s very important that new organisations that are trying to be user centric and trying to design interfaces that work for their clientele, their customers, whatever the people using it might be called, have a say in how an organisation is run and have essentially the buck stop governance at the end of it. That says they can tell designers what is needed, because they know it themselves and are involved in the process.

Our [OLH] governance structure has a lot of academics on advisory boards to tell us precisely what what’s needed so that we can go to them for consultation when we’re building things in terms of the friction point that we were discussing earlier, Ernesto. It really bugs me that endless friction you encounter when you come up with the paywall sign that says, “sign in here using your institution”, and you try and sign in using your institution, and your institution doesn’t have access. Then you go and try and find the original piece in some green Open Access repository, and it’s not there either. Then you go and ask the author, and the author emails you the paper. What kind of interface is that to scholarship? But that’s basically what we’ve got. And lots of people, as Ernesto said, think that really is the process of research. You know, it’s getting hold of the thing is as much part of the process as reading it, synthesising it and producing new research from those models. I find this very frustrating, I just think that’s pathetic. What if you could just click something and get access to this paper and you didn’t have to spend three days waiting for the author to email you back, so you can get one crucial thing for your research? That’s blocking you. That’s not doing research. Anyone can technically do what you’re doing, which is discovery. But it’s become part of this discourse that that’s what we must do to get access. That’s how long it takes. And that’s why research is so time consuming. And it just really bugs me.

In order of priority, designing social systems is almost the most crucial part of interface design.”

I just think that in order of priority, designing social systems is almost the most crucial part of interface design. It’s something that you must get right from the start. Who’s involved? Who are the stakeholders? What does your organisation look like? And it’s only then that you can get user stories, get ideas of what you’re going to actually build in whatever faces your users, whether that’s software or you know, a human interface. That’s my experience of it. And that’s why design plays a key role in what we were trying to do.

Ernesto Priego: Very useful. Thank you for your time, Martin.

Martin Eve: You’re welcome very nice to meet you all. I hope you enjoy the course. Thank you. Take care and see you all soon. Good luck!

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References and Additional Resources

Eve, Martin Paul and Priego, Ernesto (2025) Social Justice and Design Justice in Open Access. In: Design Justice Seminar, 12th March 2025, City St George’s, University of London. URI: https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/55147/

Eve, Martin Paul and Priego, Ernesto (2025) Social Justice and Design Justice in Open Access. Video recording. YouTube edit. Available via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_AZpEbRcpb0 [Accessed 14 March 2025].

Eve, Martin Paul (2014) Open Access and the Humanities: Contexts, Controversies and the Future. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI : https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316161012.

Open Library of Humanities. Resources. Available via https://www.openlibhums.org/site/resources/ [Accessed 14 March 2025].

Scott, Edward (2025) Copyright and artificial intelligence: Impact on creative industries. In Focus, 27 January 2025. House of Lords Library. Available via https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/copyright-and-artificial-intelligence-impact-on-creative-industries/ [Accessed 14 March 2025].

Knappenberger, Brian. (2014). The Internet’s Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz, video, University of North Texas Libraries, UNT Digital Library, https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc305466/ [Accessed 14 March 2025].

Nicholson, Craig (2025). “Elsevier parent company reports 10% rise in profit, to £3.2bn”. Research Professional News. 13 February 2025. Available via https://www.researchprofessionalnews.com/rr-news-world-2025-2-elsevier-parent-company-reports-10-rise-in-profit-to-3-2bn/ [Accessed 14 March 2025]

You must be logged in to post a comment.