Today is 2 de noviembre, and as such it is and always will be día de muertos1. Often an excuse not to write more is having ‘big’ topics that will become too complex and for which I won’t have the time to discuss as they deserve. Thought I could keep trying to write about some of the items in my personal library. As always, I am not promising anything.

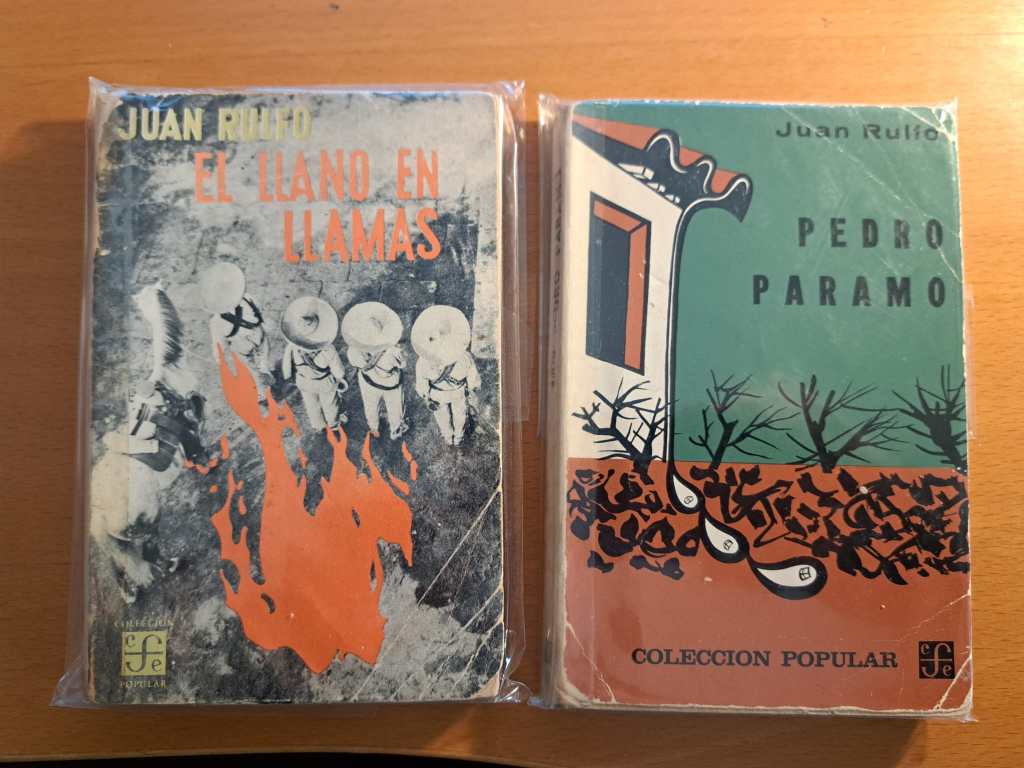

Anyway, as I started saying, “today is 2 de noviembre, and as such it is and always will be día de muertos”. It’s strange to think that today is not day of the dead for everyone everywhere, when the dead belong to all of us, when they are also everywhere, and continue to make the world go round and round. The dead propell us towards the future. Today, like many previous 2 de noviembre, I grabbed these two copies from my shelves, Juan Rulfo’s short story collection, El llano en llamas, and his short novel Pedro Páramo.

These are two of the most treasured items in my collection. These are not first editions, but a fourth and a sixth, respectively. These are the copies in which I read Rulfo first as a teenager, as both were prescribed to all of us in middle school, and after that I re-read them at university as an undergraduate, and then for sheer pleasure several times over the years. I go back to them like some people go back to their Bible or their Shakespeare- they are for me akin to reference books, sites of reassurance and temporary relief, nostalgia and inspiration. These are books that, as objects, carry magical powers, and as such are to be treated with respect. I did not always know that, but over the years these books and the stories within them became more and more powerful. They were always haunted, full of ghosts, but as time passed and I got older and things happened they became doubly, triply haunted.

The Pedro Páramo now in my possession used to belong to my father (RIP), and it still bears his signature on the first page. It is possible he bought it on the same year this sixth edition came out (1964). It was a rarity in his collection because he did not date it nor added any other notes; he used to write down exact dates and places of acquisition, and used to dedicate most of his books to my mother, even if he had originally bought them for himself, really. (Eventually, my mother would read nearly every non-technical book my father ever bought). Given I have siblings, I am not entirely sure I am the one who should have this copy right now, but the thing is I do, having brought it with me to the UK from Mexico City several years ago, as a piece of my family and my home and my country and my culture. Along El llano en llamas, it it truly is a desert island book.

El llano en llamas is a fourth edition (Colección Popular) from 1959, and I cannot fully recall how it came to my hands. This one does not have my father’s signature inside, nor a dedication (books he got us were always dated and dedicated). Instead it’s got my signature, very faint in pencil, and it’s the signature I used to do around the time I was 15 or so. I must have bought it second hand. I remember being quite snobbish at school when we were asked to read classics and fellow students brought brand-new editions of what to me seemed ancient books, so if my parents did not already have them I looked for them second hand. I felt that old books needed to be read in old editions, an affectation that I happily left behind many years ago.

Carefully flipping through these books’ yellowed pages, feeling their brittle spines that somehow still hold the pages together, it’s impossible not to be always amazed at Rulfo’s masterful craft. A perfect mash-up of the Mexican oral tradition and precise, expertly-balanced rhythm and tone. Punctuation, paragraph breaks, sentence length, word order and the rich referentiality of people’s and places’ names compose a rich universe of feeling and imagery. Of all of Mexico’s greatest writers, there is no doubt to me there’s no one like Rulfo. All of that is common place, of course.

There are writers whose works we go back to in certain times of the year: Dickens for Christmas, for example. For November, and particularly día de muertos, the go to is Rulfo. His books are part of my inheritance (the one I received; the one I hope to be able to pass on) and my heritage.

Rulfo’s literature is like an ofrenda, a celebration of life and time and place and the fading faces of those we knew. These paperbacks are my personal treasure and work like amulets and time machines. I open these books and here they are, Natalia, Camilo, Remigio, Odilón, Anacleto, Macario, la Pancha, Pedro Zamora, Comala, Luvina, Zapotlán, Talpa. But also my father, my brother in law, friends my age who’ve already departed, the places where I have lived, the old haunts. There’s no doubt in my mind that books have that power: sites of remembrance, beyond the page, beyond words and fiction, towards the present and the future.

- Can you magine feeling like you better hyperlink to a definition of, say, “Halloween”? Hopefully by now the reference is unnecessary, but just in case… ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.